– Helen Harris & Gina Figueira, StArt Art Gallery

In 2020 and 2021 Sister Namibia ran an Artists Activation project that commissioned artists to make new work related to feminism in Namibia. Working as curators on this project was an intense and gratifying experience. The parameters were broad enough that the artists we worked with did not feel restricted by them, but the direction and purpose was clear. The resulting exhibition opened online in June.

The major strength of this project was that each artist was asked to reflect on a set of circumstances that they already knew intimately: the shape, structure and feeling of living in a country and world steeped with sexism, homophobia, misogyny, patriarchy and violence. However, just because we know something well, so well that we know it in our bones, does not mean that we are already experts in talking, thinking and reflecting on it. A curator can be many things, but in the context of this project we often found ourselves in intense dialogue with the artists. Through this process a visual vocabulary emerged and this text is a reflection on this.

There are lots of directions an artist can go in when thinking about feminism in the Namibian context. Feminism is too often misunderstood as a ‘women’s issue’. While this not only ignores the complexity of gender identity, it also allows for the patriarchy to persist by relegating it to a zone of issues to be dealt with by one particular part of society, rather than by all of us. The artwork by Ndinomholo Ndilula, for example, reflects a complicated and broadened perception of feminism as a driver for equality for all cis, trans and non-binary genders. The performance titled “mASCUliN(I)TY” existed in two parts, the first of which encouraged a collaborative reading out loud (link to video) of the Namibian Combating of Rape Act (No. 8 of 2000). While this group effort got participants thinking about the often patriarchal and exclusive nature of bureaucracy, the second part of Ndilula’s performance (link to video) took on a more personal exploration of the artist’s own masculinity.

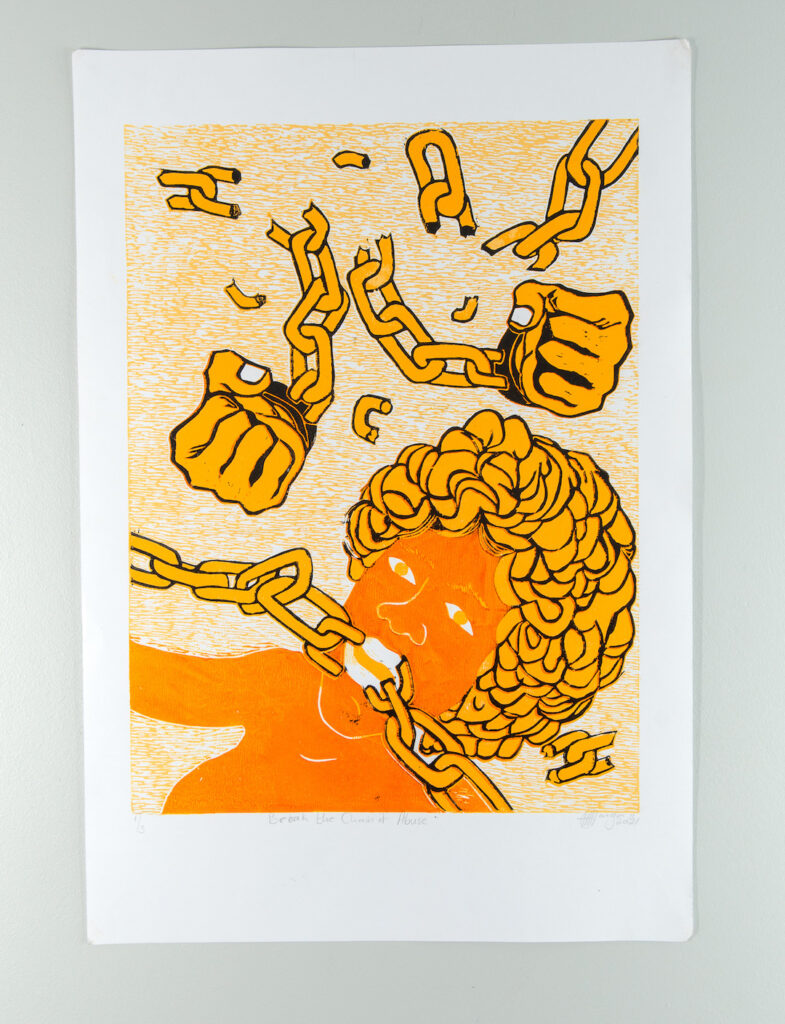

Bewise Tjonga, on the other hand, created a series of four colourful linoleum block prints that cover a range of topics but focus predominantly on body-positivity. In these works Tjonga claims space for people who have consistently been positioned as outsiders, measured against a white cisgender heterosexual ‘normal’. Claiming or taking up space is a feminist concept that encourages self determination in the face of violent and oppressive structures designed not only to maintain a social hierarchy, but also to capitalise financially on the hierarchy (think of the skin bleaching, hair removal and weight loss products constantly advertised to us). While three of the four prints depict the road to overcoming systemic violence, one of them, titled “Break the chain of abuse” deals with violence head on.

One of the many pervasive elements of patriarchal dominance is that physical violence continues to be perpetuated and normalised. Industries like advertising, film, theater and journalism, to name just a few, are often drawn to the visual elements of this violence as symbols of injustice. Visual artists are prone to do the same. When it comes to gendered violence in particular there is a strong temptation to depict women who have been beaten or are being beaten. In 2013 the National Art Gallery of Namibia hosted an exhibition called “United to end GBV” (Gender Based Violence). The exhibition took the form of an open call and displayed sixty artworks, selected out of 200 submissions, many of which featured graphic illustrations of beatings, rapes and their aftermath.

Depictions of violence are often thought to be a means by which we can shed light on something that is all too often ‘swept under the rug’. However, it is important that we ask ourselves what these images do beyond that, and how they function in the world. As artists and thinking human beings we know that visual depictions can have a strong impact, but it is also important to think about what that impact is, who is affected and how.

For people who have been violated and have personally experienced violence, seeing these depictions can be traumatic. Through these depictions, survivors can be painfully reminded of a time when they were hurt. No amount of horrific imagery will convince the perpetrators of violence that what they do is wrong; if it was that simple, society would have been rid of violence thousands of years ago. Depictions of violence do not necessarily increase our awareness of the issues at stake as we are all already highly aware of them. In fact, these depictions can result in the further normalisation of the violence that we are trying to criticize. Worse still, depictions of violence might act as a kind of affirmation for perpetrators who have already justified these actions in their own minds.

This is not to say that thinking about, processing and depicting violence has no place in art. Rather, this process is complicated and requires a great deal of care. An example can be seen in paintings by Petrina Mathews, whose process also acts as a performance (link to video). Mathew’s large scale piece “Mending the broken telephone – Fingerprints of blood”, highlights the lack of transparency and communication around the topic of sexual assault and its long term effects. Mathews’ process is a very physical one, as through it she uses her whole body: “I use my body to paint, as I can better express myself with every stroke of my hand, stomp of my feet, move in my dance and the rest of my body. My work is an expression and extension of my feelings, emotions, pains and uncomfortable truth. Every painting is filled with the colour of a past feeling and memory.” (Mathews, 2020) This physicality and the violence that it alludes to is visible in the gestural nature of the final work as well as the inevitable traces of the artist’s hands, feet and finger prints.

Other important elements to consider when making and viewing work about violence and violated bodies are the concepts of consent and dignity. Who is the person who is portrayed in these artworks, have they given permission for their image to be used and how do they feel about this depiction of them? On the other hand, if it is not a depiction of a specific individual, but rather the image of a battered body that has been used to stand in for the idea of ‘all women’ then we run the risk of creating and perpetuating a stereotype that feeds into the idea that women are weak and therefore should be dominated/saved by men. This is a stereotype that promotes the idea that women’s bodies are the kind of bodies that get hurt.

Gendered violence is an enormous and important issue that affects everyone. In the work of Ndilula, Mathews and Tjonga we can see that artists are capable of subtle interventions that deal in complex ways with the aftermath and continued presence of violence. While working on this project we started a list of questions that cultural producers might ask themselves when making work about violence. We hope that by sharing these questions here they might be useful to others in the future:

Who is the person in this work and how do they feel about this depiction of them?

How do I think a survivor of violence and a perpetrator of violence will respond to seeing this work and who is my primary audience?

What do I want to achieve with this work and is there a way to achieve this without showing a violated body?

If I can only achieve this through showing a violated body, have I got the permission of the person I am depicting or is it possible to use my own body and my own experiences instead?

Gina Figueira and Helen Harris co-founded StArt Art Gallery in 2017. They continue to run the gallery and co-curate various projects together. With a background in fine art (BFA University currently known as Rhodes 2015, MA Art Gallery & Museum Studies University of Leeds), Gina Figueira’s interest in visual culture and narrative theory have blended to form a passion for exploring and reflecting on visual memory landscapes. Helen Harris has a background in sculpture, social anthropology and contemporary curating (BFA University of Cape Town 2013, MA Contemporary Curating Manchester School of Art 2019). She is particularly interested in creating space for local knowledge production, especially in the context of writing Namibian art history.

StArt Art Gallery in collaboration with Sister Namibia have run the Sister Namibia Artist Activations project for a year over the course of 2020 and 2021. The works from this project will be shown in an online exhibition ‘We know it in our bones’ opening 17 June 2021.

Leave a Reply