- Ester Mbathera

For many of the people at Divundu settlement, ‘rape’ or ‘statutory rape’ are foreign terms that they only read or hear about in the media.

These forms of sexual abuse are not widely spoken about, despite the high pregnancy rates among young girls under the age of 15. These pregnancies are often the result of sexual relationships between young girls and older men meaning that they are legally considered statutory rape, regardless of people’s opinions or beliefs.

The area is home to a variety of civil servants, including public school teachers, nurses, and police officers. The area is also the location of the Divundu Rehabilitation Centre, which employs many officials.

Christian Matema, a teacher at a local school, blames the male civil servants who he alleges take advantage of the young girls because they are aware of the cultural norm in the area.

“They know that the parents of the young girls will never report them to the authorities because is it culturally acceptable for girls as young as 10 sometimes to be in relationship with older men,” he said. He added that as teachers in the area it is also difficult for them to report cases because some parents of survivors see nothing wrong with these types of relationships.

According to Matema, this is because the parents also financially benefit from these relationships involving their children.

“Most people who are sleeping with the kids are people who are working in the government. It’s not people from the streets. That’s a fact. They promise and give money or alcohol and once they impregnate the children they move on with their lives,” he said.

According to the Child Care and Protection Act of 2015, any person whose work concerns children has a legal obligation to report suspected abuse of any kind to a state social worker or the police. Failure to do so can result in a fine of up to N$20,000.00, 5 years in prison, or both.

Historian Shampapi Shiremo is of the opinion that parents see nothing wrong with their children being in such relationships because that is what the cultural norm has been.

According to him, this is because, in many cultures, parents used to give away their girl children to men when they reached puberty.

This was done in a controlled manner where the relationship was agreed upon by the parents, and was seen as acceptable in their societal context.

In some cases, these children were as young as the age of 10.

“It doesn’t ring in their head because the girl is according to their culture matured enough. She was not raped because he agreed to date her. Statutory rape does not exist in their cultures as far as a girl of that age who’s getting pregnant is concerned. So there needs to be some kind of education as to what statutory rape is,” said Shiremo.

In Shiremo’s opinion, some blame should be put on colonial era missionaries and current laws that abolished the traditional marriage structures. He says that the introduction of legislation around child marriage and sex work failed to consider the need to educate people (including parents) about why certain practices are harmful. People in rural areas are especially uninformed.

“We [modern society] are just doing the same thing that the missionaries and the colonial officials did. There is supposed to be sufficient education, and awareness campaigns first, to educate the people to tell them the benefits [of this legislation] and why this change is needed. I don’t think that that has been done. Maybe there is a lack of non-governmental organisations that really do that kind of work,” said Shiremo.

Anitha Mayira is a trained psychologist who moved to Divundu in 2021 after her appointment as a coach for young people facing sexual abuse in the area.

She works with the DREAMS (Determined, Resilient, Empowered, AIDS-free, Mentored and Safe) project which aims to create safe spaces for adolescent girls and young women from the age 10 to 24.

At DREAMS meetings, these young women are empowered with knowledge on how to spot gender-based violence in schools and communities.

“A safe space is a place where these girls are free to share what is happening in their lives and where we try to give advice and encouragement on how they can go about the things that they are going through. We also try to connect them to health facilities for them to get PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis] and to access contraceptives,” she said.

According to Mayira, since the establishment of the group, she has discovered that there are many cases of sexual violations which are not addressed because the perpetrators are family members.

“The young girls are suffering at the hands of their own uncle and cousin in the houses. They cannot speak up because it’s a bad thing. Or they do that because they don’t want to bring issues within the family,” said Mayira.

She explains that the challenge is also enforcement of whatever knowledge the young people get in the safe space.

Mayira added that this is because there is a lack of role models in the community.

“It’s really hard to try and help this girl child. Because parents are also involved. It’s very hard even for me as a coach to go in and bring out that child. The best thing I can do is to give them psychological support,” explained Mayira.

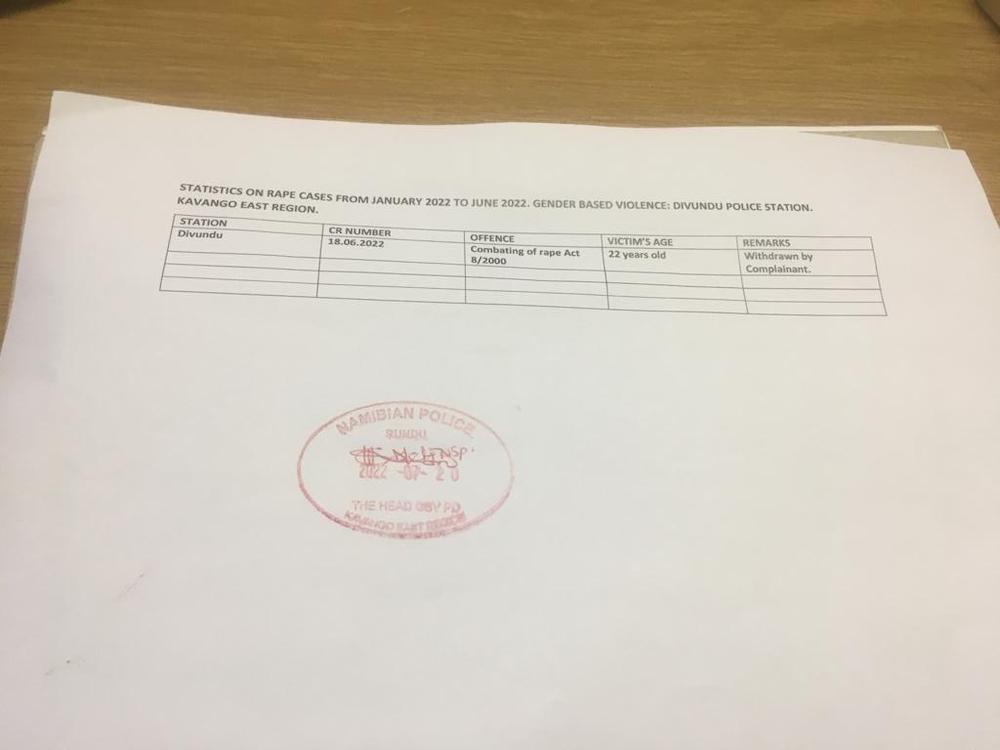

It’s not always easy to find data on statutory rape cases that have been opened; police spokesperson Kauna Shikwambi explained that the bureaucratic process means that all statistics must be approved by the Office of the Police Inspector General. However, we were able to procure records that show the sobering reality in Divundu: not one case of statutory rape was reported to police in the first half of 2022.

Ester Mbathera is a Namibian freelance journalist.

Cover image by Tingey Injury Law Firm on Unsplash