– Helen Harris & Gina Figueira, StArt Art Gallery

The art world globally has committed what Nanette Salomon terms “Sins of Omission”. Most art history canons prioritise male artists in their writings. Revised editions often try to rectify this by including sections on ‘female impressionists’ or ‘female sculptors’. This only serves to further mark the perceived difference between ‘artists’ (male artists) and ‘female artists’. It is an example of how systematic the patriarchy is in terms of consistently reinforcing a supposed ‘normal’; a normal that excludes the majority who are not wealthy, white, heterosexual, cis gender men.

All over the world feminism has been used as a way to think about, highlight and address issues of discrimination. With equality for all at its core, feminist art offers a space to challenge and make visible the oppressive structures that are pervasive but hidden, as well as a space to consider what a society that has overthrown these structures could look like. For feminism to be a real force against marginalisation, it has to be intersectional. With a long history of racial discrimination from colonial and Apartheid regimes, effective feminism in Namibia is necessarily inclusive of black and queer, non-binary people, women and men.

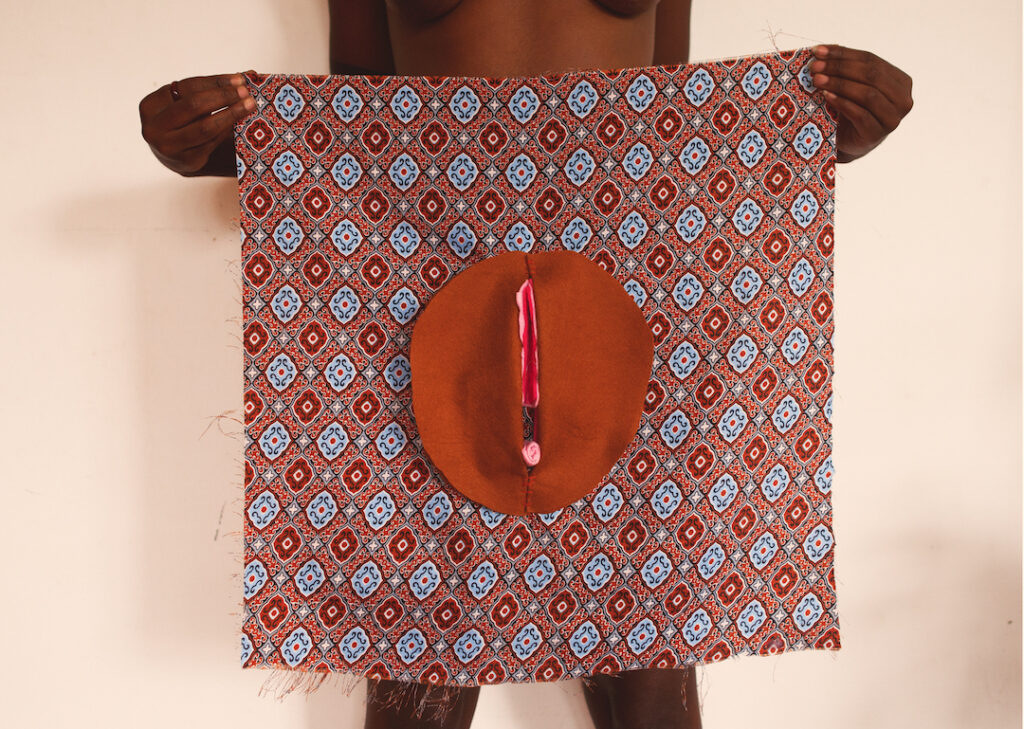

A substantial amount of feminist art seeks to claim space where space has been denied. This space exists not only in the content that artists choose to produce, but also in the act of producing. Historically, for example, the female body has been viewed through a patriarchal gaze that either violates or eroticises it, or both. The artist BIGG CLIT, who has been active in the Namibian art scene for many years, recently produced a series of photographs titled ‘Felt Pussies’. The works are fashioned out of soft pink, red and brown felt, and photographed against their own body. These soft and delicate felt-works and the photographs of them are both intimate and open; through them we see a vision of female genitalia lovingly crafted and proudly displayed. Images like this are examples of a feminist gaze which directly challenges harmful and oppressive narratives.

Similarly the multi-disciplinary artist Mel Mwevi reflects on personal experience (link to video), creating space for narratives of healing. Through her work, Mwevi tells stories and in so doing claims authorship, relating experiences which are at once personal and recognisable. Speaking about her song, and subsequent video work, ‘Take me back to the womb’, Mwevi describes it as a ‘cry’. In making this cry public through performance we are reminded of the phrase ‘the personal is political’, and are reminded that feminist ideas are often sparked by shared experiences of oppression.

For decades now, links between art and activism have been clear. In many Southern African fights against oppressive regimes such as Apartheid, for example, artist studios like the Medu Ensemble worked alongside political activists to produce art related to the movement. More recently, links between art and protest have been clear in, for example, the work of Sethembile Msezane at the 2015 Rhodes Must Fall protests in South Africa.

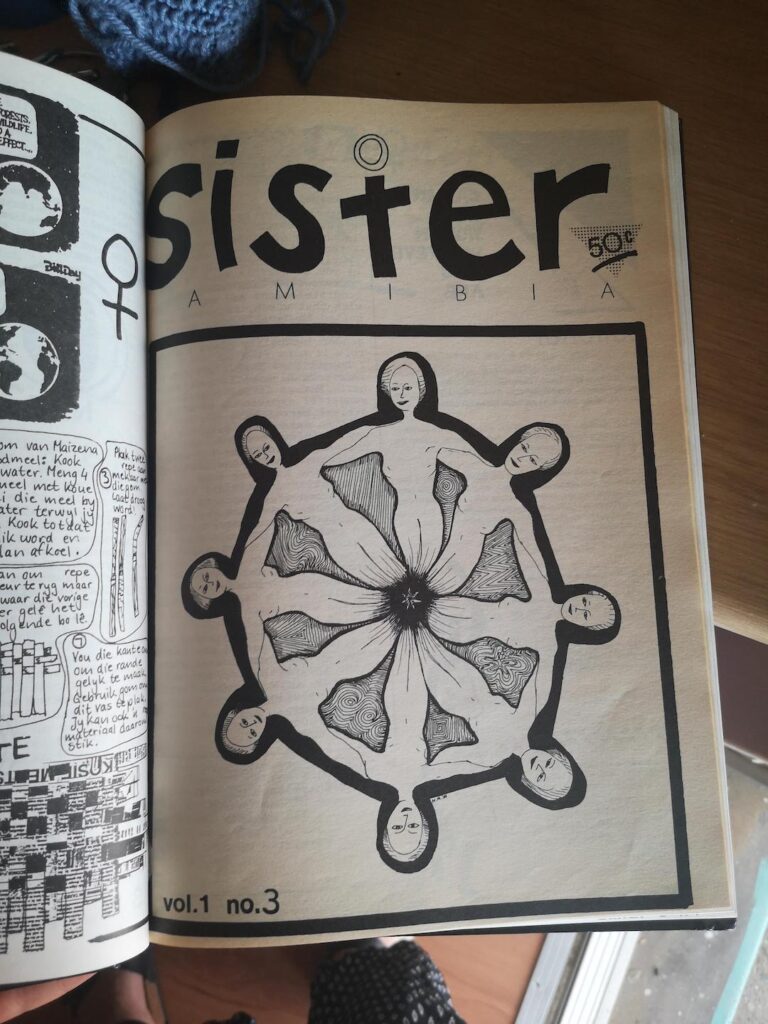

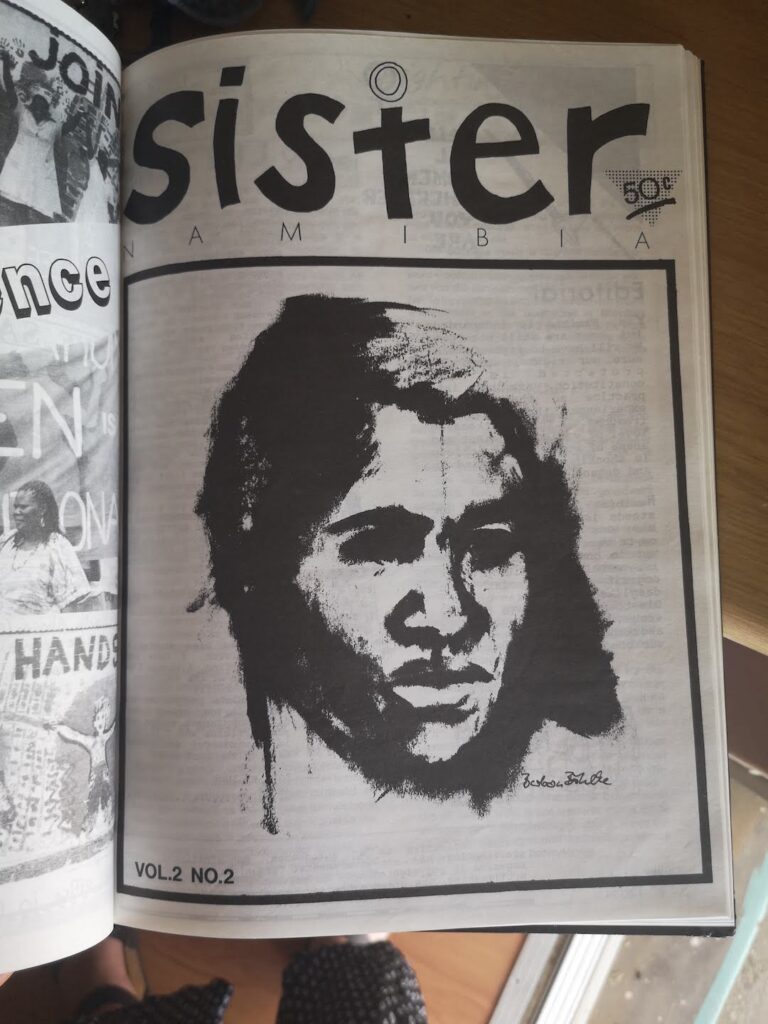

The term ‘Artivism’ or ‘Artivist’ encapsulates the often shared agenda of art and activism, which are in fact often one and the same. The Sister Namibia magazine has created a great archive of artivists working to contribute to discussions around Namibian independence as well as racial and gender equality. Flipping through the pages of old Sister magazines, artworks by artists and educators like Nicky Marais and Barbara Bohlke can be seen. The history of the feminist and activist movements in Namibia and their link to the artistic community, as detailed in the Sister Namibia magazine archives, has laid the foundation for the ongoing push for equality.

Vitjitua Ndjiharine delved into the Sister Namibia magazine archive and created illustrations that reflected the, still very salient, themes of Sister Namibia’s earliest editions. Inspired by the illustrations from the 1990’s and early 2000’s Ndjiharine was struck by the continued relevance of the messages being shared. Ndjiharine created illustrations in a similar style, using a hand-drawn aesthetic that was then engraved into mirrors. Ndjiharine’s work calls for reflection, asking everyone who sees the work to see themselves in the messages: “Don’t replace my rights with your religion”, “Keep politics out of my body”, “Say hello to the new dope me”, “We are still at war”, “To uplift one of us it takes all of us” etc.

Art as activism carries on all over the world today. In Namibia, with recent protests against SGBV and racial disrimination, contemporary artists are adding their visuals and voices to the dialogue. Hildegard Titus chose to celebrate important feminists and activists in the large-scale work “This is what Namibian Feminism Looks Like”. Installed in late 2020 on a billboard along Nelson Mandela Avenue in Windhoek, this work is a prime example of taking up space. When watching the billboard go up, Titus noted “I never thought I would see the word ‘Feminism’ in such huge letters in Windhoek.” The background of the artwork reads over and over again, “Protect Women, Support Women, Love Women, Believe Women, Transwomen are women”. In a country with such high rates of SGBV and a society (as well as a legal system) that systematically harms women and members of the LGBTQI+ communities, this artwork makes a statement that is even larger than the billboard itself.

The history of Namibian art is written in fragments. Various academics and artists have chipped away at the enormity of the project of writing this history, with large pockets of silence hanging over various aspects of this history. One of these largely un-narrated gaps is the history of feminism in art. The Sister Namibia magazine, stretching from the 90’s to the present, is an ongoing archive that touches on and quietly celebrates the relationship between art and activism in Namibia. By holding space for these artists and activations, we see the narrative opening up and expanding. ‘Sins of Omission’ cannot be undone retrospectively, but we can do the work of sitting with these archives to appreciate the work that has been done while committing to and adding to them at every opportunity.

Gina Figueira and Helen Harris co-founded StArt Art Gallery in 2017. They continue to run the gallery and co-curate various projects together. With a background in fine art (BFA University currently known as Rhodes 2015, MA Art Gallery & Museum Studies University of Leeds), Gina Figueira’s interest in visual culture and narrative theory have blended to form a passion for exploring and reflecting on visual memory landscapes. Helen Harris has a background in sculpture, social anthropology and contemporary curating (BFA University of Cape Town 2013, MA Contemporary Curating Manchester School of Art 2019). She is particularly interested in creating space for local knowledge production, especially in the context of writing Namibian art history.

StArt Art Gallery in collaboration with Sister Namibia have run the Sister Namibia Artist Activations project for a year over the course of 2020 and 2021. The works from this project will be shown in an online exhibition ‘We know it in our bones’ opening 17 June 2021.

Leave a Reply